Dr Elena Dvoskina's paper at the Medium Aevum Symbolicum Seminar

On 19 March 2018 Dr Elena Dvoskina offered a paper ‘Scientia bene modulandi from Aurelius Augustine to Alexey Losev’.

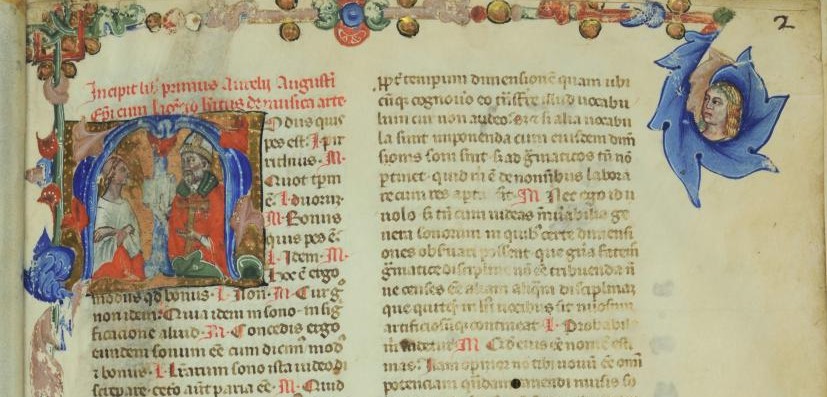

The paper was primarily occasioned by the recent launch of Dr Dvoskina’s Russian translation of the six volumes of Augustine’s De Musica, and addressed one of the central frames of thought developed in them—the concept of modulatio.

Augustine’s De Musica (On Music, AD 387–390) was originally conceived as part of his cycle on the school curriculum. Ever since Varro, compendia of this kind enjoyed wide popularity among erudite authors writings in Latin. For early Christian thinkers, working within this intellectual tradition offered opportunity to engage with ancient thought about the practice and theory of music while sketching novel approaches to the incipiently Christianized discipline of composing and performing music. Augustine’s treatise, however, failed to take off as a widely read contribution to the academic field, thwarted as it was by the early success of Boethius’ De Institutione Musicae (On the Principles of Music)—to be extended in the second Christian millennium by Guido of Arezzo’s Micrologus. De Musica’s effective failure to win popularity may have been down to its somewhat idiosyncratic thematic scope. Rather than discussing pitch and melody, Augustine focused on rhythm.

Already in Augustine’s lifetime the reception of the De Musica was somewhat tentative. It did get to be copied, but only in part: only Book Six dealing with the ‘rhythms of perception’ went down into contemporary manuscript tradition. Medieval intellectuals, in their accustomed heeding to the authoritative statements of church fathers, would be equally drawn to the concluding part of the treatise; reading it in its entirety was a rarity (Roger Bacon is one example). It was not until the Renaissance that the whole text of Augustine’s composition attracted wider academic scholars, when it did, however, it was not to last long.

Phrasing from opening sections of the De Musica enjoyed quite a fate of its own, however. Famously, Augustine opines ‘Music is knowledge of good modulation’ (Musica est scientia bene modulandi). The definition is first offered a century earlier in Censorinus’ De Die Natali (On the Date of Birth) and arguably goes down to Varro’s textbook which does not survive. Augustine is to take credit, however, for the broad acceptance of this definition up to the 16th century.

The Latin modulatio is conventionally used to refer to musical harmony, coherence, and order. Thus, e.g. 3rd-century Roman grammarian Marcus Plotius spoke of modulatio chororum as choral singing which is harmonised and coherent in terms of pitch. Augustine puts it to a new use as he offers another definition ‘Music is knowing the correct movement’ (Musica est scientia bene movendi). The concepts of modulation and movement are therefore interconnected. The link between the two is further brought out in Augustine’s definition of modulation as ‘a kind of skill in movement’ (quaedam peritia movendi). From among ancient thinkers, Aristoxenus of Tarentum exhibits similar views on music.

The concept of ‘movement’, as elaborated by Aristotle, is well fit to describe movement in chronological progression. Augustine in De Musica develops a phenomenological framework within which is approached as simultaneously a proportion and ‘becoming’, i.e the transition from one proportion to the next one. The correct transition of this sort lies at the heart of music as an academic discipline which can therefore be defined as knowledge and contemplation of time aesthetically reconstructed.

Augustine’s angle on music rapidly lost its historically specific conceptual content. While in early middle ages, e.g. in Bede’s De Orthographia (On Correct Spelling) we still see modulatio used as a Latin equivalent of the Greek rhythmos, in later authors the rhythmical sense fades out and modulation acquires increasingly practical connotations. For example, Heinrich Glarean in his Dodecachordon (AD 1547) relies on Augustine’s phrasing ‘for practical reasons’ while falling back on Boethius’ definitions in more theoretical strands of his thought (in his discussion of the human ability to discern pitch differences through physical senses and in the mind). The original emphases embedded into Augustine’s definition are ultimately eliminated the when translated into vernacular languages. Lampadius, the author of the Compendium Musices (Compendium of Music) (AD 1537), for example, narrows the sense down to the ‘art of singing’ in the vernacular German (Teyto eine singe kunst). In modernity, modulatio is typically understood simply as the expansion of the musical scale and pitch outside the chronological frame.

Dr Dvoskina concluded her talk by giving stimulating insights into how Augustine’s tradition of musical thought was appropriated in the works of early 20th century Russian theorizers and philosophers of music (G. Konyus, B. Yavorkiy. A. Losev etc.). This served as a relevant recapitulation of the points she made about medieval developments and rounded off the discussion of an extended historical trajectory of a late antique philosophical and musicological framework.